Ahead of his appearance at Buxton International Festival, author and historian Peter Parker reflects on the criminalisation of gay men in post-war Britain — and the quiet acts of resistance that helped change the law.

How did this period lay the ground for the modern gay rights movement? A lot of people assume gay rights began in the 1970s or 80s, but people were fighting for them — risking their freedom — in the 1950s. It wasn’t just MPs or figureheads. It was ordinary men with extraordinary nerve — refusing to be invisible.

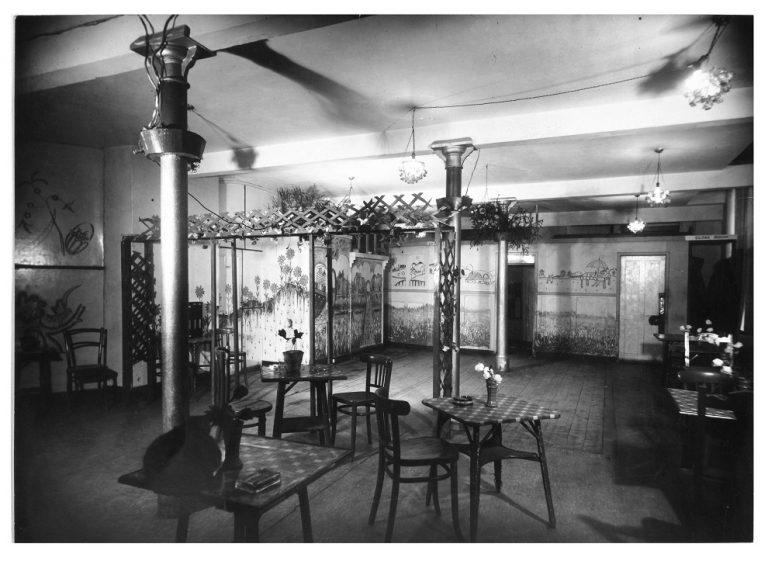

What was the public atmosphere like in 1950s Britain? Post-war Britain was gripped by a national panic. People linked homosexuality with everything from juvenile delinquency to the collapse of the British Empire. The media stoked the fear while fuelling voyeurism, running endless headlines about guardsmen, scandals and arrests. There was this simultaneous fear and fascination.

How did the law enable blackmail and fear? The law was so irrational and so poorly drafted that it enabled what was called the blackmailers’ charter. Just the suspicion of being gay was enough to be threatened. If someone knew or even suspected, they could ruin your life — and often did.

Were the police protecting men from this abuse? On the contrary. The police discovered that if they went into public lavatories and arrested men, it was very easy to get a conviction and it looked good on the score sheet. Plainclothes officers were even deployed to entice men into criminalised behaviour. It was open entrapment.

Were there moments of hope during this period? Absolutely. There were people writing letters to the Spectator and the New Statesman under their own names — that was an act of real bravery. In one blackmail case involving two airmen, the public actually booed the blackmailers and cheered the gay men.

What did activism look like before marches and Pride? Some of the earliest gay liberation was actually in courtrooms — not winning, necessarily, but standing up and being counted. Activism didn’t always mean marching. Sometimes it meant refusing to plead guilty. Some of these men were arrested, humiliated, even imprisoned — but still came back to fight for others.

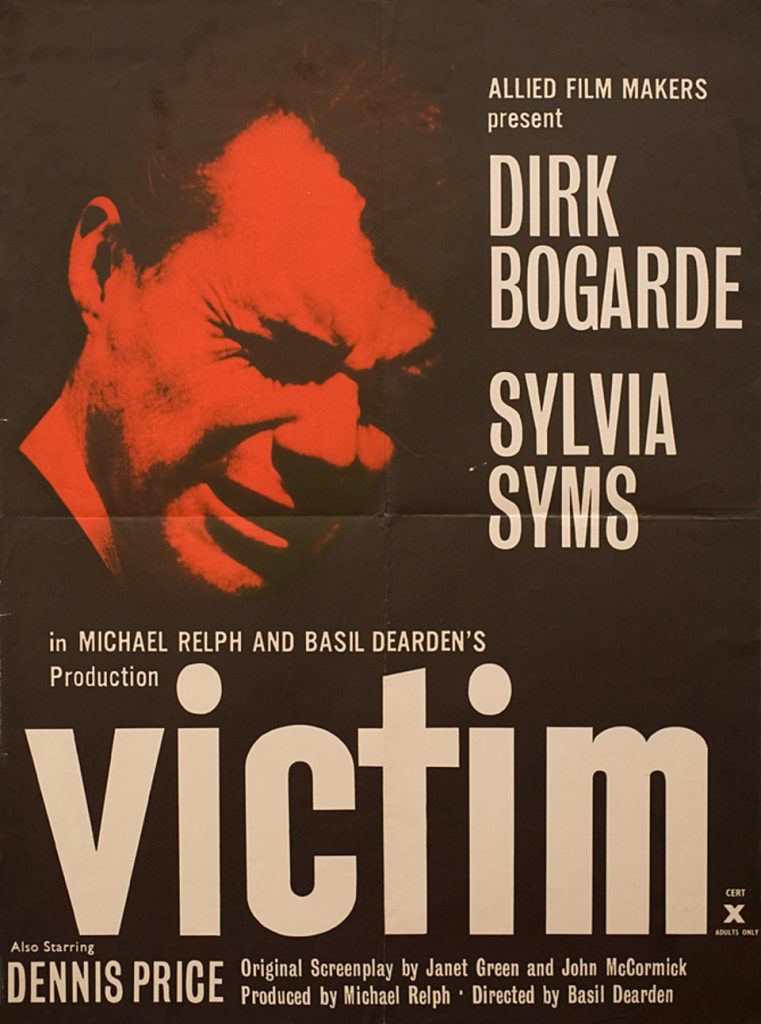

Why is the film Victim still so important? It was the first mainstream film to show that gay men were vulnerable to blackmail — and to portray that with sympathy rather than ridicule. Actor Dirk Bogarde knew exactly what he was doing. That film helped change the law. The reaction was immediate. People wrote in saying, ‘I didn’t know this happened.’ It opened a lot of eyes. And crucially, it gave ordinary people a way to talk about homosexuality without embarrassment. It made it human.

What should we take away from these stories today? It’s not just about shame and fear. There was defiance. There was humour. And there was courage — in courtrooms, in letters, and in the very act of survival.