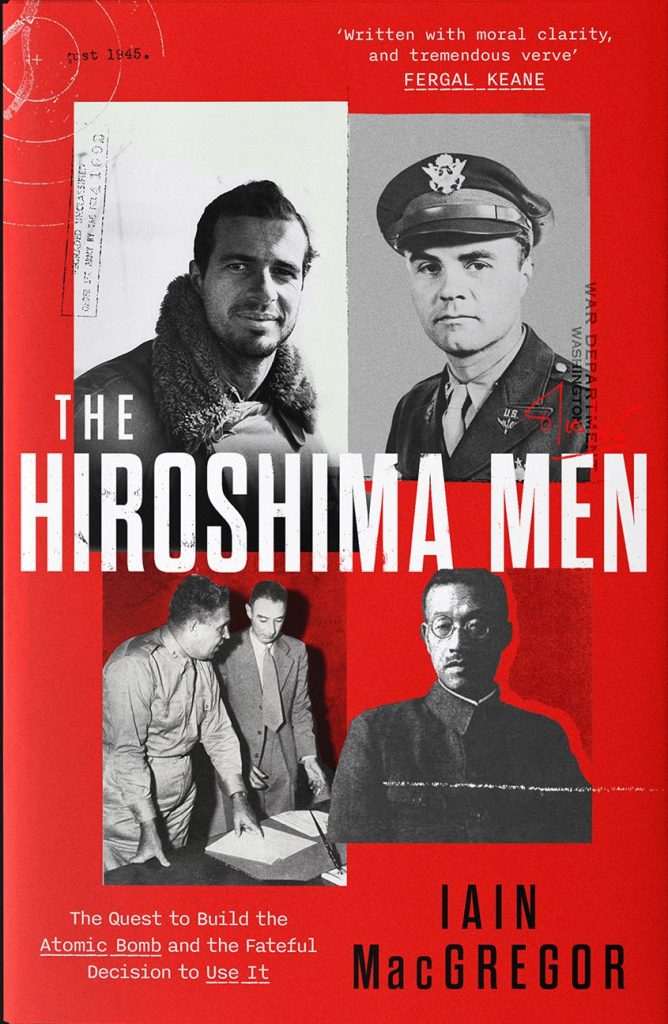

Ahead of his appearance at the Buxton International Festival, Iain MacGregor shares insights from his new book The Hiroshima Men — a powerful, unsettling account of the individuals at the centre of the world’s first nuclear attack and the enduring human cost.

What led you to write this book?

I was researching The Lighthouse of Stalingrad at the Volgograd Museum during lockdown when I found a diorama of Hiroshima’s destroyed atomic dome—a gift from Hiroshima to Volgograd in the 1970s. That strange tribute planted the seed of a hidden story, and I began wondering about the people who lived through it.

You explore how the Hiroshima story was controlled after the bombing. What happened?

Once American forces occupied Japan, they set up a press department that included a censorship office. Reports about radiation sickness—what Japanese doctors were documenting—were immediately shut down. Newspapers were suspended, and medical findings were buried. The aim was simple: contain the narrative, not just the blast’s radioactive fallout.

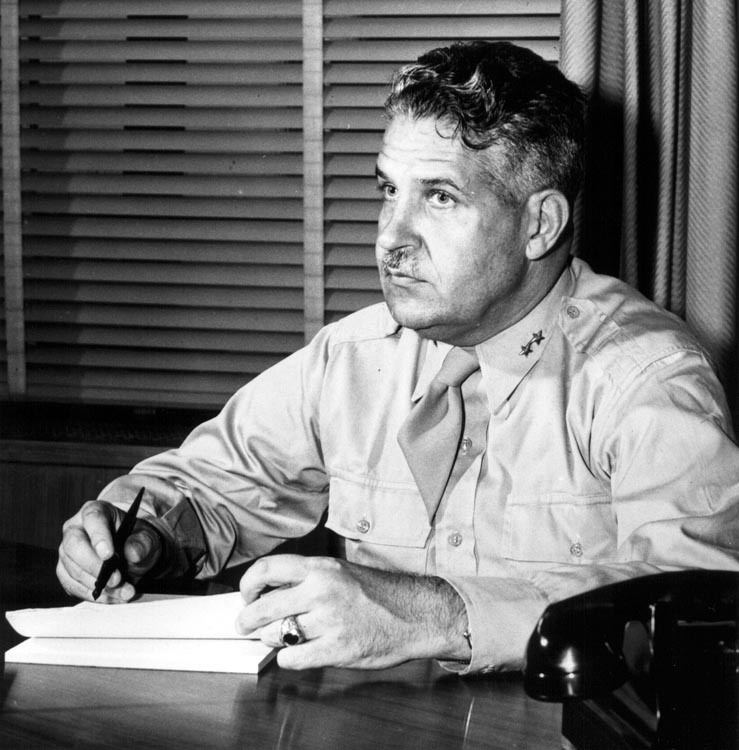

General Leslie Groves, the man who oversaw the Manhattan Project and built the bomb, led that effort. Alongside Oppenheimer, he dismissed these reports: “They don’t know what they’re talking about.” The U.S. military strategy was to shape public perception just as much as it had shaped the weapon.

So how did the truth emerge?

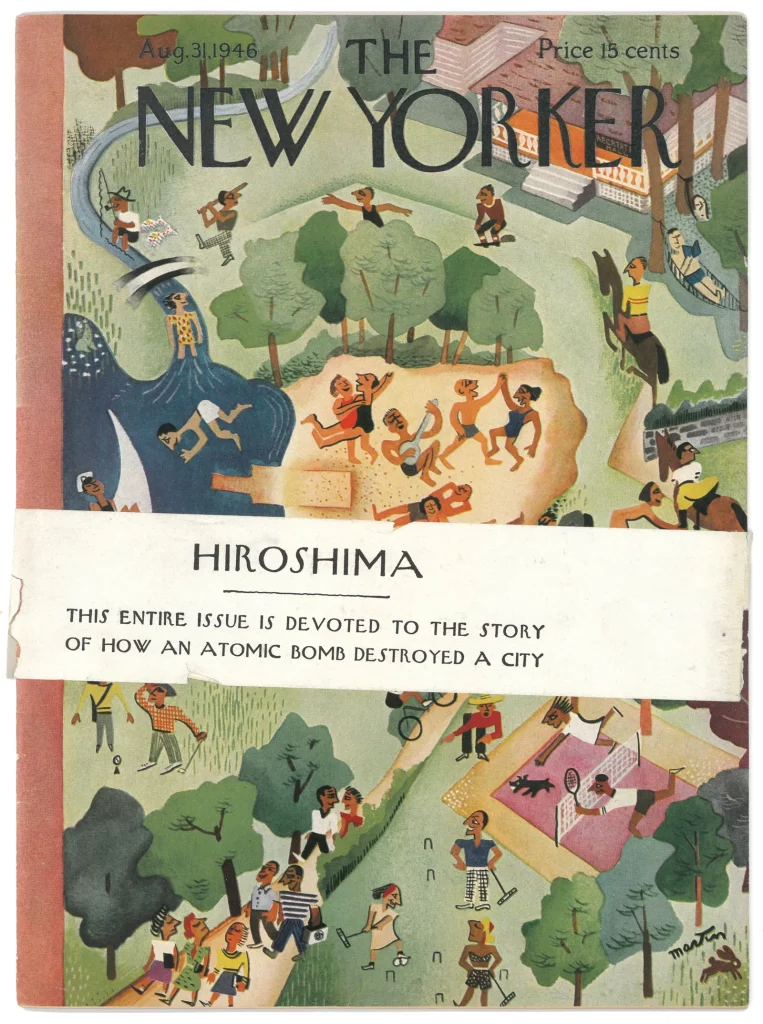

Journalist John Hersey slipped through. He’d written a favourable memoir of MacArthur during the war, which helped him fly under the radar. He quietly reached Hiroshima, interviewed more than 30 survivors, and wrote a 30,000‑word piece. The New Yorker made the extraordinary decision to devote an entire issue to it—prepared secretly, with a dummy edition for the staff. When it dropped, it shook the world.

What did Groves think of the article?

Surprisingly, he approved it. He recognized its devastating power—and thought that exposing the horror would actually strengthen the case for nuclear deterrence. He even told a congressional committee bizarrely that radiation sickness is “a very pleasant way to die.” In his mind, the public needed that fear to justify more weapons, not fewer.

Did Hersey’s story make a difference?

Absolutely. It sold more than 300,000 copies within a few weeks in the U.S. Major newspapers backed it, and the BBC dramatized it within a month. Once the human cost was laid bare, authorities could no longer bury it. Hersey changed the global narrative—where no official report ever could.

You also focus on Japanese voices. Tell us about Senkichi Awaya.

Senkichi Awaya was the mayor of Hiroshima when the bomb fell—yet today he’s virtually unknown. His children published his memoir in the 1960s, and only one copy survives in the Tokyo National Library. We had to read it on-site, page by page. Awaya was a Christian pacifist and patriot who believed in law, not militarism. He opposed child labour, resisted the rising army, and later was forced out of retirement to lead Hiroshima. He and his wife were killed in the blast. When I asked the Peace Memorial Museum director if he knew Awaya’s name, he didn’t. That was all the confirmation I needed: his story deserved to be told.